Middle Turbinate Osteoma

Article information

Abstract

Osteoma is the most common benign tumor of the paranasal sinuses. Turbinate osteomas are very rare and only four middle turbinate, one superior turbinate and one inferior turbinate osteoma cases have been reported. We present a rare case of osteoma of the left middle turbinate in a patient presented with unilateral nasal obstruction and epiphora that was removed endoscopically, and conduct a literature review on turbinate osteomas arising from different turbinates, their symptoms and management.

INTRODUCTION

Osteomas are the most common benign tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, with an incidence that ranges between 0.43-1% (1, 2). They occur most commonly within the frontal sinus (52%), followed by the ethmoid (22.0%), the maxillary sinus (5.1%), and the sphenoid (1.7%) (1). It is very rare for an osteoma to arise in the nasal cavity or turbinates. Only four middle turbinate (2-5), one superior turbinate (6) and one inferior turbinate osteoma cases (7) have been reported in the literature to date.

We report an unusual case of middle turbinate osteoma associated with left-side nasal obstruction, epiphora and post nasal discharge in a patient managed successfully by endoscopic surgery (ES).

CASE REPORT

A 41-year-old woman was referred to the department of otorhinolaryngology at the Rasool Akram Hospital with a two-month history of progressive left nasal obstruction, epithora, and post nasal discharge. She had no history of facial trauma or nasal surgery. Her past medical history was unremarkable. She had no family history of osteoma or colonic malignancies.

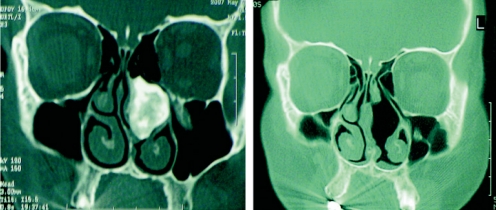

Endoscopic examination revealed a mass completely blocking the left nasal cavity of bony hard consistency. Computed tomography (CT) scan showed a circumscribed bony mass integrated laterally to the left middle turbinate that exerts pressure on the medial maxillary wall. There was no cribriform plate involvement (Fig. 1). Routine laboratory tests were normal. No extension to the skull base was observed.

The osteoma was totally extirpated subsequently without damaging the surrounding structures by ES under general anesthesia. The mass was released gently from its attachment to the middle turbinate using a sickle knife. Although the mass measured 3.0×2.7 cm in diameter, it passed through the left nostril without the need for further incision (Fig. 2). Examination of the histologic sections revealed a dense, mature, predominantly lamellar bone, consistent with osteoma (Figs. 3 and 4). The postoperative course was uneventful. She remained completely symptom-free 3 months following surgery (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

Osteoma is a benign, slow-growing tumor. While it is a common tumor of paranasal sinuses that is found more frequently in the maxillary, ethmoidal and frontal sinuses (1), it is very rare in the nasal cavity.

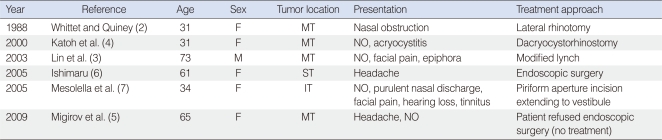

Beside the turbinates, the nasal septum can also be the origin of nasal osteoma (1). Reported cases of turbinate osteoma in the literature are summarized in Table 1. The etiology of osteomas arising from the paranasal sinuses can be embryological, traumatic or infective. Osteomas can also be a part of Gardner's syndrome, an autosomal dominant disease characterized by intestinal polyposis, osteomas, cutaneous and soft tissue tumors. In affected individuals, the risk of developing colon cancer approaches 100%. On average, osteomas are detected 17 years before colon polyps begin to appear (8, 9). In turbinate osteomas, no associated history of facial trauma or nasal surgery had been reported, and paranasal sinus infection appears to be the result of sinus meatal obstruction due to mass effect of the tumor (3).

Paranasal sinus osteomas may occur at any age, but usually present between the second and fourth decade, with a slight male predominance (3). However, in the seven reported turbinate osteomas cases, including this, six cases were found in women and only one case in man (Table 1).

The majority of osteomas are asymptomatic in the early stages and are diagnosed incidentally during radiological examination for the other conditions. In symptomatic cases, the most common symptoms are progressive headache and chronic inflammation of the adjacent mucosal membranes (10). Other symptoms are due to osteoma pressure effect on the adjacent structures. The most common symptom in turbinate osteomas is nasal obstruction. In this case, the patient presented with nasal obstruction, epithora and post nasal discharge. The tumor mass was located in the left nasal cavity associated with complete obstruction. In addition, there was nasolacrimal duct induced epiphora secondary to tumor compression. The other presenting symptoms of turbinate osteoma are listed in Table 1.

Osteomas can be detected by plain radiograph. However, it does not give detailed information of the lesion and it is not conducive for surgical interventions. Although CT scan is an effective modality for the evaluation of osteomas, capable of detecting the extent of osteoma and invasion of the adjacent structures, namely the anterior cranial fossa, cribriform plate, and the orbit that may improve surgical decision making (6).

In osteoma arising from the paranasal sinuses, surgical removal is indicated if it extends beyond the boundaries of the sinus, continues to enlarge, localizes in the region adjacent to the naso-frontal duct, or if signs of chronic sinusitis are present, regardless of size in symptomatic tumors (6-8).

Surgical approaches are classified into external, endoscopic drill-out, and combined endoscopic and external procedures (10). Although endoscopic removal is the preferred modality, the open approach should be considered to manage tumor involvement of the cribriform plate and frontal sinus.

In osteoma arising from the turbinates, the tumor is more accessible and endoscopic removal carries less risk, and is easier compared to sinus osteomas. It is therefore important to diagnose nasal osteoma when it is small in size, follow it up and resect it when it is of a size that can be resected successfully by ES, as in the present case.

Based on the fact that ES carries low risk in the management of nasal osteoma, except when the cribriform plate is involved, and it is technically easier compared to endoscopic removal of sinus osteomas and smaller tumors and leads to better cosmetic outcomes, it appears clinically relevant to remove nasal osteomas at the time of diagnosis.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.