Clinical Implications of Mandible and Neck Measurements in Non-Obese Asian Snorers: Ansan City General Population-Based Study

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

Anthropometric abnormalities of the mandible and neck may contribute to snoring in non-obese Asians. The study evaluated the clinical implications of mandible and neck measurements in non-obese Asian snorers.

Methods

The external mandible and neck measurements (neck circumference, two lengths of neck, mandibular body angle, and lengths of mandibular ramus and body) were compared between snorers and non-snorers in a sample of 2,778 non-obese Koreans (1,389 males, 1,389 females) aged 40 to 69 years (mean, 48.47±7.72 years).

Results

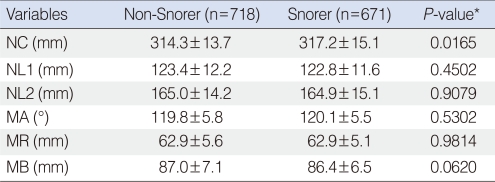

The overall prevalence of snoring was 64.7% (899/1,389) and 48.3% (671/1,389) in non-obese male and female subjects, respectively. In non-obese males, snorers had significantly a greater neck circumference (P<0.0001) and shorter mandibular body length (P=0.0126) than non-snorers. In non-obese females, snorers had significantly greater neck circumferences (P=0.0165), compared with non-snorers. However, there were no statistically significant differences in other variables between non-snorers and snorers.

Conclusion

Anthropometric abnormalities of the mandible and neck, including thick neck circumference in both genders and small mandible size in males, may be relevant contributing factors to snoring in non-obese Asian snorers.

INTRODUCTION

Snoring is a vibratory sound generated in the upper airway by the uvula, soft palate, tongue and pharyngeal walls during respiration while sleeping. Approximately 40% of the general population snores and snoring frequently accompanies obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (1). Habitual snoring may be associated with various severe complications such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular diseases (2-8).

Obesity or excessive weight is a major contributing factor in sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), including snoring and OSA (9). Obese patients usually show a deposition of fat around the neck, decreased functional residual capacity, reduced chest wall compliance and changes in neural compensatory systems that preserve airway patency. These features can contribute to narrowing of the upper airway inlet and an increase in collapsibility of the pharyngeal muscle (9-11). In obese patients, upper airway narrowing by soft tissue enlargement may be mainly associated with the development or aggravation of SDB, while in non-obese patients craniofacial bony abnormalities may be primarily related with SDB (12).

Asian patients with OSA display more severe illness, compared with Caucasian patients for a given age, gender, and body mass index (BMI) (13). Furthermore, Far-East Asian patients have more distinct craniofacial bony abnormalities and are less obese than white patients, when matched for the degree of severity of OSA (14).

It is necessary to determine the anatomical contributing factors that could be easily identified by manual measurements in non-obese snorers, especially in the Asian population. We hypothesized that the anthropometric bony and soft tissue abnormalities of the mandible and neck may contribute to snoring that is frequently linked with OSA in non-obese Asians. To investigate this hypothesis, the clinical implications of manually-measured anthropometric data for the mandible and neck were assessed in non-obese Asian snorers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The subjects were a subgroup of the population in the Korean Health and Genomic Study (15). Among the 5,020 participants living in Ansan city who were initially examined, a subset of non-obese subjects with a BMI (kg/m2) <25 was selected. Exclusion criteria were obesity, as indicated by a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, subjects who were unaware of whether she/he snored and failure to complete the questionnaire for any reason. Demographic information collected from the subjects during the interview included age, gender, weight in kg, height in meters and BMI. The protocols of this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board, Ansan Hospital, Korea University.

Snoring

The non-obese subjects were divided into two groups: snorers and non-snorers. A snorer was someone who snored at least one night per week, based on self-report and confirmation by their bed partner or other family member. To determine the reproducibility of the questionnaire, 200 participants 40-69-years-of-age were retested two weeks after the first test. The kappa value for the question on snoring was 0.73 (15).

Mandible and neck measurement

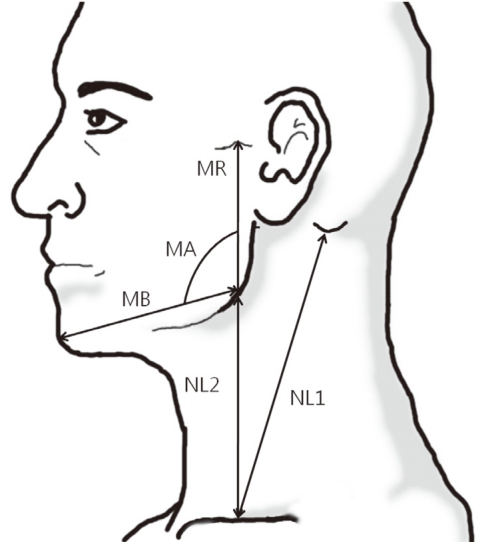

External mandible and neck measurements were obtained for all subjects while each subject stood upright and gazed forward (Fig. 1). Anthropometric indices of all subjects were measured by 10 raters who were trained by a standardized protocol. The following were measured: neck circumference (NC, distance in mm around the neck at the level just below the most prominent portion of the thyroid cartilage, i.e., Adam's apple), the length of neck 1 (NL 1, distance in mm from the mastoid tip to the mid-portion of the ipsilateral clavicle), length of neck 2 (NL 2, distance from the mandibular angle to the mid-portion of the ipsilateral clavicle), mandibular angle (MA, angle [°] between the mandibular body and the mandibular ramus), length of mandibular ramus (MR, distance in mm from the mandibular angle to the temporomandibular joint) and length of mandibular body (MB, distance in mm from the mandibular angle to the chin). Each measurement was taken three times to minimize measurement error, with the reported results representing the average.

Statistical analyses

Demographic data were compared between the snorer and non-snorer groups using independent t-tests; while the anthropometric data were compared using ANCOVA to correct for age and height. SAS ver. 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used to conduct the statistical analyses. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

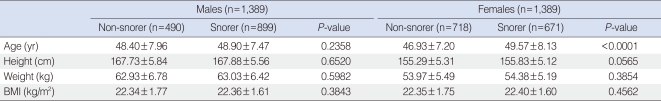

RESULTS

Of the 5,020 participants living in Ansan city who were initially examined, a subset of 2,778 non-obese subjects with a BMI < 25 was selected (55.34% of the total). The subjects were 40-69-years-of-age (mean, 48.47±7.72 years). The number of males and females were equal (n=1,389). The overall prevalence of snoring was 64.7% (899/1,389) in males and 48.3% (671/1,389) in females. The demographic and baseline characteristics of both the snorers and non-snorers are summarized in Table 1.

Manual external measurements of the mandible and neck, taken from the male and female Asian subjects, are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Snorers in both genders had a significantly greater NC, and snorers in males had significantly shorter MB lengths, when compared with non-snorers. However, there were no statistically significant differences in other variables between non-snorers and snorers in both genders.

DISCUSSION

The study evaluated the clinical implications of mandible and neck measurements in non-obese Asian snorers within a large group that is considered to be representative of the general population. The findings indicate that bony and soft tissue abnormalities of the mandible and neck, including thick NC in both genders and small size of mandible in males, may be relevant contributing factors for snoring.

The pathogenesis of SDB, including snoring and OSA, has been linked to anatomical, neuromuscular, ventilatory and combined factors (11). Among these, anatomical factors that contribute to SDB are relatively easy to find from a routine physical examination, while neuromuscular or ventilatory factors can be harder to discern when subjects are awake. For this reason, studies have used craniofacial, or head and neck measurements, related to structural narrowing of the upper airway (16, 17). Similarly, this study was designed to determine whether manually-measured, anthropometric data for the mandible and neck could be usefully linked with snoring frequently connected with OSA in non-obese Asians.

NC is an important measurement that is reflective of soft tissue deposition within the upper airway region. NC correlates with the severity of SDB, and greater NC is related to increasing of the upper airway soft-tissue such as tongue and soft palate (18). These outcomes closely echo the results of our present study, which revealed that both non-obese Asian male and female snorers have a significantly thicker NC, as compared to non-snorers.

Presently, non-obese Asian snorers had a significantly shorter MB than non-snorers males. These results are consistent with the findings of previous studies, which reported that mandible size is a very important risk factor related with SDB (19, 20). One of these earlier studies reported highly significant correlations between magnetic resonance imaging measurements and direct measurements made with a caliper and planimeter in the isolated human mandible area (19). In addition, the authors reported that the occurrence of OSA was related to the size of the region enclosed by the mandible, as well as to a subject's weight. Moreover, a meta-analysis of the literature, evaluating the craniofacial bony contributing factors, revealed a clinically significant association between MB and diagnostic accuracy for OSA (20). The presently-revealed shorter MB in the non-obese male snorers may be reflective of a relatively narrower oropharyngeal passage, which may result in a greater degree of crowding of the oropharyngeal soft tissue. In the non-obese females, this difference in MB was not observed to a significant degree between snorers and non-snorers. This may be attributed to differences in the bony structure and the dynamic collapsibility of the upper airway between males and females. It may also be influenced by anthropometric or hormonal differences existing between males and females.

The strength of this study is in the large number of subjects enrolled from a community-based general population, in which the repeated measurement of each parameter minimized measurement error. There are a few limitations in this study. Inter-rater or intra-rater measurement reproducibility was not assessed. However, this possibility of measurement error is likely low, since the measurement was conducted by a rater who was trained with a standardized protocol and was recorded to the nearest 1 mm. Data on the frequency of snoring was obtained from self-reports and was confirmed by the bed partner or family member. Furthermore, to compensate for this limitation, the reproducibility of the question responses on snoring was examined; the results showed that their reproducibility was high.

Among the several manually-measured anthropometric variables for the mandible and neck of non-obese Asian subjects, the NC of snorers in both non-obese males and females was greater than that of non-snorers, and that MB in non-obese male snorers was significantly reduced. The results suggest that anthropometric abnormalities of the mandible and neck, including thick neck circumference in both genders and a small jaw in males, may be relevant contributing factors for snoring in non-obese Asian snorers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (budgets 2001-347-6111-221, 2002-347-6111-221).

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.