Follicular Thyroid Carcinoma Presenting as Bilateral Cheek Masses

Article information

Abstract

Mandibular metastasis of thyroid carcinoma is extremely rare. We present the case of a 46-year-old woman who had bilateral huge cheek masses that had grown rapidly over several years. Intra-oral mucosal tissue biopsy and imaging work-up including computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging were performed and the initial diagnosis was presumed to be central giant cell granuloma. Incidentally detected thyroid lesions were studied with ultra-sonography guided fine needle aspiration and diagnosed as simple benign nodules. Due to continuous oral bleeding and the locally destructive feature of the lesions, we decided to excise the mass surgically. To avoid functional deficit, a stepwise approach was performed: Firstly, the larger left mass was excised and the mandible was reconstructed with a fibular free flap. The final pathologic diagnosis was follicular thyroid cancer. Postoperative I-131 thyroid scan and whole body positron-emissions-tomography were performed. Right side mass was revealed as a thyroid malignancy. Multiple bony metastases were detected. Since further radioactive iodine therapy was required, additional total thyroidectomy and right side mandibulectomy with fibular free flap reconstruction was performed. The patient also underwent high dose radioactive iodine therapy and palliative extra-beam radiotherapy for the metastatic lumbar lesion. Follicular thyroid carcinoma should be considered as a differential diagnosis for mandibular mass lesions.

INTRODUCTION

Mandibular metastasis of thyroid carcinoma is extremely rare. We present the case of a 46-year-old woman who had bilateral huge cheek masses that had grown rapidly over several years. Intra-oral mucosal tissue biopsy and imaging work-up including computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging were performed and the initial diagnosis was presumed to be central giant cell granuloma. The final pathologic diagnosis was follicular thyroid cancer. Follicular thyroid carcinoma metastasizes most commonly to the lung and bone. The hematogenous route is most often involved, either by way of the systemic circulation or occasionally through the paravertebral plexus. Lymphatic spread, although less common, is also possible. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first bilateral mandibular metastases report in the literature. Clinicians should consider thyroid carcinoma as an appropriate differential diagnosis for bilateral mandibular masses.

CASE REPORT

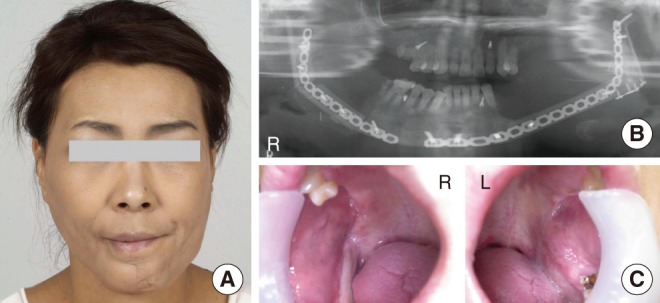

In April 2007, a 46-year-old woman was referred to the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Seoul National University Hospital for evaluation and further treatment of bilateral huge cheek masses. The masses had grown intra-orally and filled the whole oral cavity, disturbing normal mastication so that the patient had lived on soft or fluid diet (Fig. 1). Although her dentist had recommended surgery 5 years earlier, she was reluctant of undergoing operation and had repeatedly delayed the surgery. Over the 5 years, the disease was aggravated and the size of the mass increased progressively with intra-oral bleeding occurring intermittently.

Preoperative gross appearance of the patient (A) and intraoral masses (B). She had huge bilateral cheek tumors. The lesions had grown intra-orally and filled the whole oral cavity.

Imaging work-up including neck computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. Large bilateral masses showed strongly enhanced solid tumors originating from the mandible which resulted in expansile destruction and erosion of both sides of the mandilble (Fig. 2A). These lesions extended from the body to the condyle of the mandible. Intra-oral mucosal deep tissue biopsy from the left side mass was conducted and it was reported as an inflamed granulation tissue with necrosis. Therefore, the initial diagnosis was presumed to be central giant cell granuloma. Incidentally detected thyroid nodules on the CT scan were studied with ultra-sonography guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology and the results were simple benign nodules (Fig. 2B). Though the cheek masses had locally destructive features, there was no evidence of malignancy. Due to the patient's hesitancy about having an operation, we initially tried intra-lesional triamcinolone injection rather than surgical resection. Intra-lesional steroid injection is the alternative treatment of central giant cell granuloma, especially in large lesions, which may compromise vital structures [1]. The patient was treated once a week with an injection of 40 mg of triamcinolone into both mandibular tumors. The triamcinolone injections were not effective except transient size reduction and the treatment was terminated after a total of 3 injections on each side. Due to continuous oral bleeding and the aggravated locally destructive feature of the lesion, we decided to surgically excise the mandibular masses. Since the lesion involved bilateral mandible widely, to avoid a functional deficit of the mandible, such as a mastication, we decided to perform a stepwise approach:

Bilateral lesions were aggravated and the size of the mass increased rapidly. Large bilateral masses showed strongly enhanced solid tumors originating from the mandible which resulted in both expansile destruction and erosion of the mandible. These lesions extended from the body to the condyle of the mandible (A, B). Incidentally detected thyroid lesions were studied with ultra-sonography guided fine needle aspiration cytology and the results were simple benign nodules (C, black arrow head).

The larger left mass was excised with the mandible that resected from 1st premolar to condyle. The involved buccal mucosa was also resected upto anterior to the retromolar trigone. The mandible and the buccal mucosa were reconstructed with osteocutaneous free flap using the left fibula and a skin paddle of fibular flap, in order to minimize the functional deficit, the intact uninvolved condyle was re-aligned onto the reconstructed mandible. Surprisingly, the final pathologic diagnosis turned out to be highly differentiated thyroid malignancy with involvement of the mandibular bone and perimandibular soft tissue. Immunoreactivity for thyroid transcription factor-1 of the left mandibular tumor revealed thyroid origin of the tumor (Fig. 3A, C). The thyroid malignancy was possibly either follicular or papillary carcinoma but due to the borderline feature of the mass, a definite diagnosis could not be made. Conclusively, we proposed that the remnant lesion on the other side of mandible would have the same pathology and also suggested two possible diagnoses. One was bilateral mandibular metastases of an occult thyroid malignancy. The other possible diagnosis was bilateral ectopic thyroid malignancies with normally located thyroid glands, less likely. Therefore, additional work-up procedures for the right side mass and distant metastasis were performed. Although the result of FNA from the right mandible mass was reported as no evidence of thyroid origin or malignancy, the thyroid gland and the right side mass were revealed as a thyroid malignancy and multiple bony metastases including lumbar spine and femur neck were detected on I-131 thyroid scan (Fig. 4A) and whole body fluoro-deoxyglucose positron-emissions-tomography (PET) (Fig. 4B). Two weeks later after the first surgery, total thyroidectomy was performed for definite diagnosis of the disease and high dose radioactive iodine therapy (RAI). The thyroid nodule was revealed as follicular thyroid cancer (Fig. 3B). The confirmative diagnosis was follicular thyroid cancer with systemic metastasis involving both sides of the mandibule. Although immediate high dose RAI should follow, endocrinologist recommended surgical resection of the remnant right mandibular mass in case of possible local complication by radioactive iodine accumulation during high dose RAI. Six months later, right side mandibulectomy with fibular free flap reconstruction was planned. During the 6 months, due to the risk of pathologic fracture, metastatic lesions in the lumbar and femur were treated with extra-beam radiotherapy, 24 Gy and 30 Gy respectively.

The left mandibular tumor showed highly differentiated thyroid malignancy (A: H&E, ×100). The thyroid nodule contains mildly differentiated thyroid follicles and demonstrates atypia of the follicular epithelium with blood vessel invasion (B: H&E, ×400). Immunoreactivity for thyroid transcription factor-1 of the left mandibular tumor revealed thyroid origin of the tumor (C: Immunostain, ×400).

On thyroid scan (A) and positron emission tomography (B), after right side hemimandibulectomy, the thyroid gland and right side mass were revealed as a thyroid malignancy and multiple bony metastases involving the lumbar spine and femur neck were detected.

The second surgery, right side hemimandibulectomy and osteocutaneous free flap reconstruction using the right fibula was conducted 7 months later. In order to save the mastication ability of the patient, much care was taken to preserve the masseter and pterygoid muscles as much as possible (Fig. 5C). During the postoperative 1 year, she has been treated two times with 200 mCi RAI. No evidence of local recurrence has been suspected. Mastication ability was saved without any problems and the postoperative aesthetic result was satisfying (Fig. 5A, B).

DISCUSSION

Metastasis of thyroid carcinoma to the mandible is a very rare event and to the best of our knowledge, this presented case is the first case presenting bilateral mandibular metastases of follicular thyroid cancer. In previous papers, it has been reported that cases of metastases to the maxilla or mandible compose less than 1 percent of all metastatic bony lesions, regardless of origin [2-4]. The mandible rather than the maxilla is the more common metastatic site, due to its higher incidence of retained embryonic red bone marrow [5]. The ramus and the angle of the mandible are the most frequent metastatic site, owing to their superior vascularity [6]. The site of tumor and the characteristics such as an indolent tumor growth were the major causes for initial misdiagnosis as a central giant cell granuloma. The central giant cell granuloma is a relatively common lesion found mostly in young adults. It affects females more frequently than males in a ratio of 2:1. It occurs almost exclusively in the maxilla and mandible. The mandible is involved more often than the maxilla. The lesion produces a firm, painless expansion of the involved area, and the cortical plates are thinned, but usually not perforated. The radiographic features consist initially of a unilocular and later, as the lesion enlarges, a multilocular radiolucency with well-defined borders that may displace or resorb tooth roots [1].

Recently reviewed 114 cases of metastatic jaw tumors showed that the most common primary tumor site was the breast, regardless of sex. Other primary sites, in order of frequency, were the lung, the male reproductive system, the colorectal region and the thyroid [7]. Other studies reported that mandible metastasis with breast origin was most common and that with thyroid origin was possible. Various papers have published similar results [8-11]. Follicular thyroid carcinoma metastasizes most commonly to the lungs and bone. The hematogenous route is most often involved, either by way of the systemic circulation or occasionally through the paravertebral plexus. Lymphatic spread, although less common, is also possible [8,9]. If multiple metastatic foci result, as in our case, the hematogenous route is much more likely [10].

Symptoms of mandibular metastasis usually include pain, swelling, loosening of the teeth, trismus, ulceration and bleeding, as experienced by our patient. Dental problem such as loosening of the teeth is also possible [11]. Clinicians should be aware of mandibular metastasis mimicking inflammatory condition such as periodontitis, periapical lesions or osteomyelitis. With the appropriate medical history, a primary oral soft tissue malignancy with osseous invasion should be considered, as well as a possible second primary malignant mandibular bony lesion. A tumor of the mandible, such as ameloblastoma, should also be ruled out [10]. However, if a history of a thyroid carcinoma can be determined, the suspicion of a thyroid metastasis must be raised sufficiently. The growth rate of a thyroid carcinoma may be slow, and the metastasis in the bone or lung may be undetected for long periods of time. Therapy for the metastatic site generally consists of surgical resection and either RAI or external-beam radiation. Long-term prognosis is poor, with an average survival rate of 40% for 4 years after the diagnosis of metastasis [8]. It is thought that bony metastasis has a poorer survival rate than pulmonary metastasis. However, there is some evidence proving that resection of a solitary bony metastasis, along with a total thyroidectomy, may provide better survival. This may enhance the uptake and increased effectiveness of postoperative RAI in dealing with other occult systemic metastasis [12].

Although this is a rare occurrence, the clinician's index of suspicion must remain high to the possibility that one is dealing with a metastatic thyroid carcinoma until it is proven otherwise. In the differential diagnosis of mandible lesion, metastatic malignancies should always be considered.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.