INTRODUCTION

Nasal septal perforation is an anatomic defect of the cartilaginous and bone tissues of the nasal septum. Asymptomatic nasal septal perforation does not require any treatment, but if these patients present with symptoms such as crusting, a sensation of nasal obstruction, bleeding, headache, dryness and whistling, then treatment is needed to relieve the symptoms (1). The patients who have nasal septal perforation and mild symptoms usually require medical treatment such as nasal irrigations and ointments (1-3). Septal buttons may also be used in these patients (4). If these treatments are unsuccessful, then surgical treatment is recommended. Many approaches and techniques to repair nasal septal perforations have been reported (1, 5-9). Despite these various techniques, the closure of nasal septal perforation is a still challenging and difficult procedure. The purpose of this paper is to report on our surgical technique and the results of this treatment for nasal septal perforations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From May 2001 to March 2008, 14 patients with symptomatic nasal septal perforation were enrolled in this study and they were retrospectively reviewed. The patients (12 males and 2 females) had a mean age of 41.3 yr (range: 19 to 60 yr), and they had no underlying disease and the diagnosis of perforation was confirmed by nasal endoscopy with using a 0° telescope during the pre-operative period. The mean perforation size was 15 mm (range: 7 to 20 mm), and the perforations were located at the cartilaginous portion.

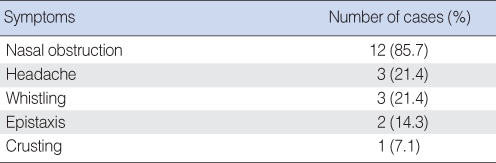

The presenting symptoms were nasal obstruction (in 12 cases), headache (in 3 cases), whistling (in 3 cases), recurrent epistaxis (in 2 cases) and crusting (in 1 case) (Table 1). The etiologies of the nasal septal perforations were septoplasty complication (in 12 cases), aggressive cauterization (in 1 case) and idiopathic (in 1 case) (Table 2).

Surgical technique

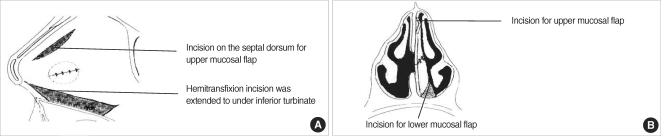

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia. A graft of temporalis fascia was obtained from the patient. The nasal septal mucosa was infiltrated with 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. The surgical approach began with a hemitransfixion incision and the incision was extended laterally to under the inferior turbinate (Fig. 1) to make a lower mucosal flap for easy advancement without tension. The mucoperiosteal flap was then elevated. It is important to avoid tearing the nasal mucosal flap during this step. Once the flap was completely elevated, another incision was made on the septal dorsum to make the upper mucosal flap. The upper flap was transposed downward and the lower flap was also advanced upward, and then the two mucosal flaps covered the perforation. The flaps should advance to cover the perforation without tension. The naked septal dorsum and nasal floor were left uncovered. The flaps were then sutured together with 5-0 vicryl. On the contralateral side, we did not make a flap to cover the perforation. The fascia graft, trimmed to size, was next inserted through the hemitransfixion incision. The silastic sheets were designed to cover the graft and the area of the exposed septal dorsum and the nasal floor. The silastic sheets were sutured and the nasal cavities were packed with Merocels®. The packs were removed 2 days after surgery and the silastic sheets were removed at about 4 weeks postoperatively.

RESULTS

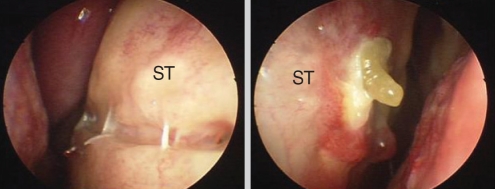

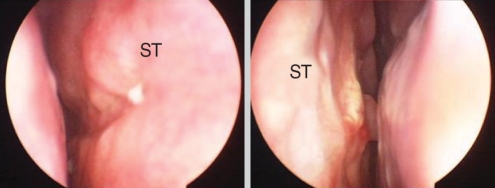

The follow-up periods of the patients ranged from 3 to 23 months (mean follow-up period: 8 months). After the silastic sheets were removed, the uncovered septal dorsum and nasal floor were almost recovered with the nasal mucosa (Fig. 2, 3). There were no complications after the operations. For our surgical technique with 14 patients, 12 cases (85.7%) of septal perforation were closed. In two cases (14.3%), we could not achieve complete repair of nasal septal perforation. Although two of the 14 patients had a small remaining perforation (about 2-3 mm), the patients did not have any significant symptoms related to the perforation and they didn't undergo revision surgery.

DISCUSSION

Nasal septal perforations after septoplasty have been reported to have an incidence of approximately 1% (10). Typically, when the mucoperichondrium is disrupted on both side of the cartilage, then the nasal septum is deprived of its blood supply and so a nasal septal perforation is formed (7). There are numerous causes of nasal septal perforation, including trauma, nasal surgery (septoplasty), digital manipulation, drugs and neoplasms (11). In our cases, septoplasty was the most common cause of nasal septal perforation. The key to manage septal perforation is preventing their occurrence.

Nasal septal perforations are usually an incident finding in asymptomatic patients on physical examination. The nasal septal perforation that's located posterior tends to be asymptomatic. In contrast, the anterior perforation often presents with symptom such as crusting, a sensation of nasal obstruction, bleeding, headache, dryness and whistling. Among them, a sensation of nasal obstruction was the most common symptom for our cases.

Surgical treatment of symptomatic nasal septal perforation often leads to unsatisfactory results, and so many approaches and techniques have been used to repair nasal septal perforations. The open rhinoplasty approach with an external columellar incision can achieve wide exposition of the septum, but this procedure leaves an external scar (11, 12). The midfacial degloving also allows excellent visualization of the septal perforation and it is a good procedure for larger perforations, but it is an extensive procedure (6). The endonasal approach has been reported on by other authors (2, 7, 13). The endonasal approach technique is less invasive and it leaves no external scars, but it is more difficult technique due to the limited exposure of the operative field.

Our surgical technique with the endonasal approach has no limitation of exposure of the operative field during surgery and it has the advantage of no external scars. The use of nasal endoscopy ensures excellent and precise exposure of the operative field.

In addition to the surgical approach, numerous flaps have been previously described such as labial-buccal mucosal flaps (14), inferior turbinate flaps (2) and nasal mucosal flaps (3, 5, 15). Nasal mucosal flaps are commonly used flaps, and using nasal mucosal flaps allows for maintaining normal nasal physiology. They can be mono- or bi-pedicled, and the bipedicled flap is more preferable because of the increased vascular supply (16).

The hemitransfixion incision is routinely used to expose the operative field (17). In the previously reported pervious cases, the hemitransfixion incision was made in the contralateral side because of the fear of compromising the vascular supply to the mucosal flap. In our cases, we made a hemitrasfixion incision on the ipsilateral side of the mucosal flap and we extended this incision laterally to under the inferior turbinate. It made a lower flap, almost like a monopedicled flap, for supplying blood from the posterior pedicle if we just consider supplementing the vascular supply of the mucosal flap. It also made advancing the mucosal flap much easier without any tension. We were also afraid of compromising the vascular supply, but we did not observe that any of our cases suffered from an insufficient vascular supply. For our cases, we made upper and lower mucosal flaps for complete closure of the nasal septal perforation without any tension. However, in the case of a small perforation, the lower mucosal flap could be big enough to cover the perforation.

Many graft materials are interposed between septal flaps and the most frequently used autograft is the temporalis fascia. We also used the temporalis fascia. One side was covered with the repaired septal flaps and the other side was left uncovered, and this was covered several months later with nasal mucosal epithelium (Fig. 2, 3).

In our technique, only the unilateral nasal mucosal flap was made to repair the nasal septal perforation. Some authors have reported success with using a unilateral flap (2, 18, 19). The unilateral nasal mucosal flap has the advantages of avoiding enlargement of the perforation and developing of any other perforation during the operation; it also maintains the normal nasal physiology and shortens the operation time with performing a one stage procedure.

As well as the surgical technique, postoperative care is important for obtaining a better result. In our hospital, we used postoperative nasal packing to help achieve adequate adhesion of the mucosal layers. In addition, the silastic sheets remained in the nasal cavities for about 4 weeks without any complication such as secondary infection. Silastic sheets help to reduce the crust on graft materials or the nasal septal mucosa, thereby allowing the nasal septal mucosa to quickly recover.

Among the 14 patients in our cases, two cases (14.3%) of septal perforation were not completely closed. The remaining septal perforations were located at the anterior portion of the original nasal septal perforation. It is relatively hard to suture the anterior portion of a nasal septal perforation. We believe that the inadequate suturing at the anterior portion of the nasal septal perforation may have been the cause of the remnant perforations.

CONCLUSIONS

The lower monopedicled flap for easy advancement is a viable procedure for achieving closure of nasal septal perforations. Furthermore, the unilateral mucosal flap is enough to close septal perforations with a high success rate. It has the advantages of shortening the operative time, no external incision and it can help avoid creating any other perforation during the operation. This technique is useful, but it requires extensive experience in endoscopic surgery. This technique could be a good alternative for repairing nasal septal perforations.